Story

In February 2003, Daniel Libeskind was named the winning designer in the international contest to rebuild the World Trade Center. His strikingly original design for Freedom Tower used a design process that could be characterized as design by dictator. Meaning a design driven by one person. The product was a twisting, asymmetrical abstract homage to the Statue of Liberty. Despite Libeskind’s victory, the design was far from final. The requirements for the building were extraordinarily complex, the consequences of getting the design wrong were unacceptable, and the number of powerful stakeholders was large. Given these conditions, Freedom Tower was destined to be designed by committee.

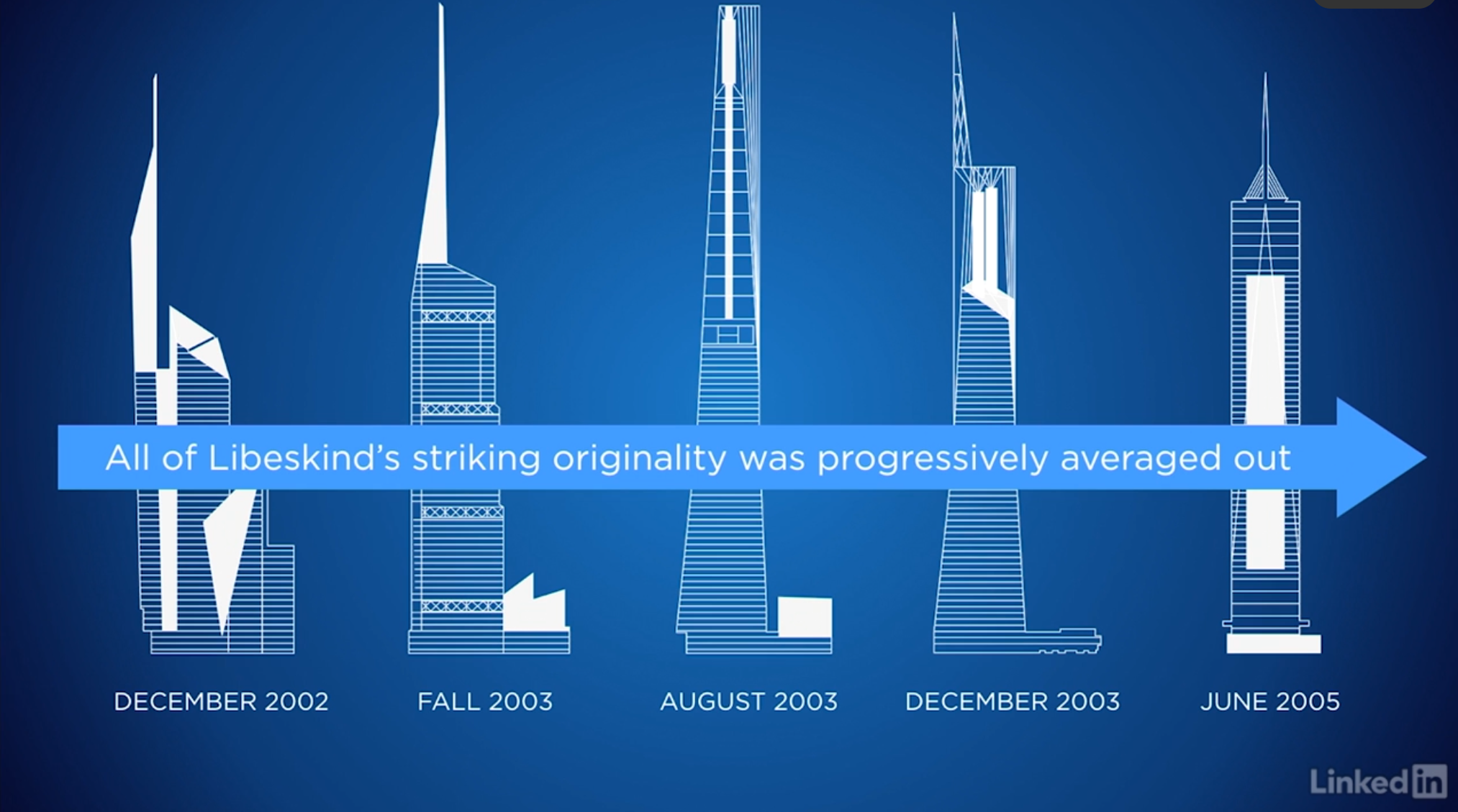

As the design process plodded along year after year, iterating repeatedly through the various commercial, engineering, security, and political factions, all of Libeskind’s striking originality was progressively averaged out. What remained was a fairly straightforward, symmetrical, tube-skyscraper with a spire on top. Or, as New York Times Architecture Critic Michael Kimmelman phrased it, “An opaque, shellacked, monomaniacal skyscraper “with no mystery, no unraveling of light, “no metamorphosis over time, “nothing to hold your gaze.” And he concludes with, “It implies a metropolis bereft of fresh ideas.”

Takeaway

It is a commonly held view that good design results when projects are driven by an autocratic leader, and bad design results when projects are driven by democratized groups. Many find this notion of an alpha leader romantically appealing, believing that great design requires a tyrannical “Steve Jobs” at the helm to be successful. This notion is, at best, an oversimplification, and in many cases it is simply incorrect.

Design by dictator is preferred when projects are time-driven, requirements are relatively straightforward, consequences of error are tolerable, and stakeholder buy-in is unimportant. It should be noted that with the exception of inventors, celebrity designers, and entrepreneurial start-ups, virtually all modern design is at some level design by committee (e.g., clients, brand managers, etc.). The belief that great design typically comes from dictators is more myth than reality.

Design by committee is preferred when projects are quality-driven, requirements are complex, consequences of error are serious, or stakeholder buy-in is important. For example, NASA employs a highly bureaucratized design process for each mission, involving numerous working groups, review committees, and layers of review from teams of various specializations. The process is slow and expensive, but the complexity of the requirements is high, the consequences of error are severe, and the need for stakeholder buy-in is critical. Virtually every aspect of mission technology is a product of design by committee.

Design by committee is optimal when committee members are diverse, bias and influence among committee members is minimized, local decision-making authority is encouraged operating within an agreed upon global framework, member input and contributions are efficiently collected and shared, ideal group sizes are employed (working groups contain three members, whereas review boards and decision-making panels contain seven to twelve members), and a simple governance model is adopted to facilitate decision making and ensure that the design process cannot be delayed or deadlocked.

Consider design by committee when quality, error mitigation, and stakeholder acceptance are primary factors. Consider design by dictator when an aggressive timeline is the primary factor. Favor some form of design by committee for most projects, as it generally outperforms design by dictator on most critical measures with lower overall risk of failure — bad dictators are at least as common as good dictators, and design by dictator tends to lack the error correction and organizational safety nets of committee-based approaches. Autocracy is linear and fast, but risky and prone to error. Democracy is iterative and slow, but careful and resistant to error. Both models have their place depending on the circumstances.

Learn More

- LinkedIn Learning

- Page 74 of Universal Principles of Design