Story

In 1959, the industrialist Henry Kremer created a series of challenges and rewards centered on human-powered flight. It was basically the XPRIZE of its day. The first Kremer prize offered 50,000 pounds for the first human-powered plane to fly a figure eight around two markers one half mile apart. The challenge was formidable. Dozens of teams tried and failed for more than 17 years, each spending months designing and building their planes just to have them crash minutes after a test flight.

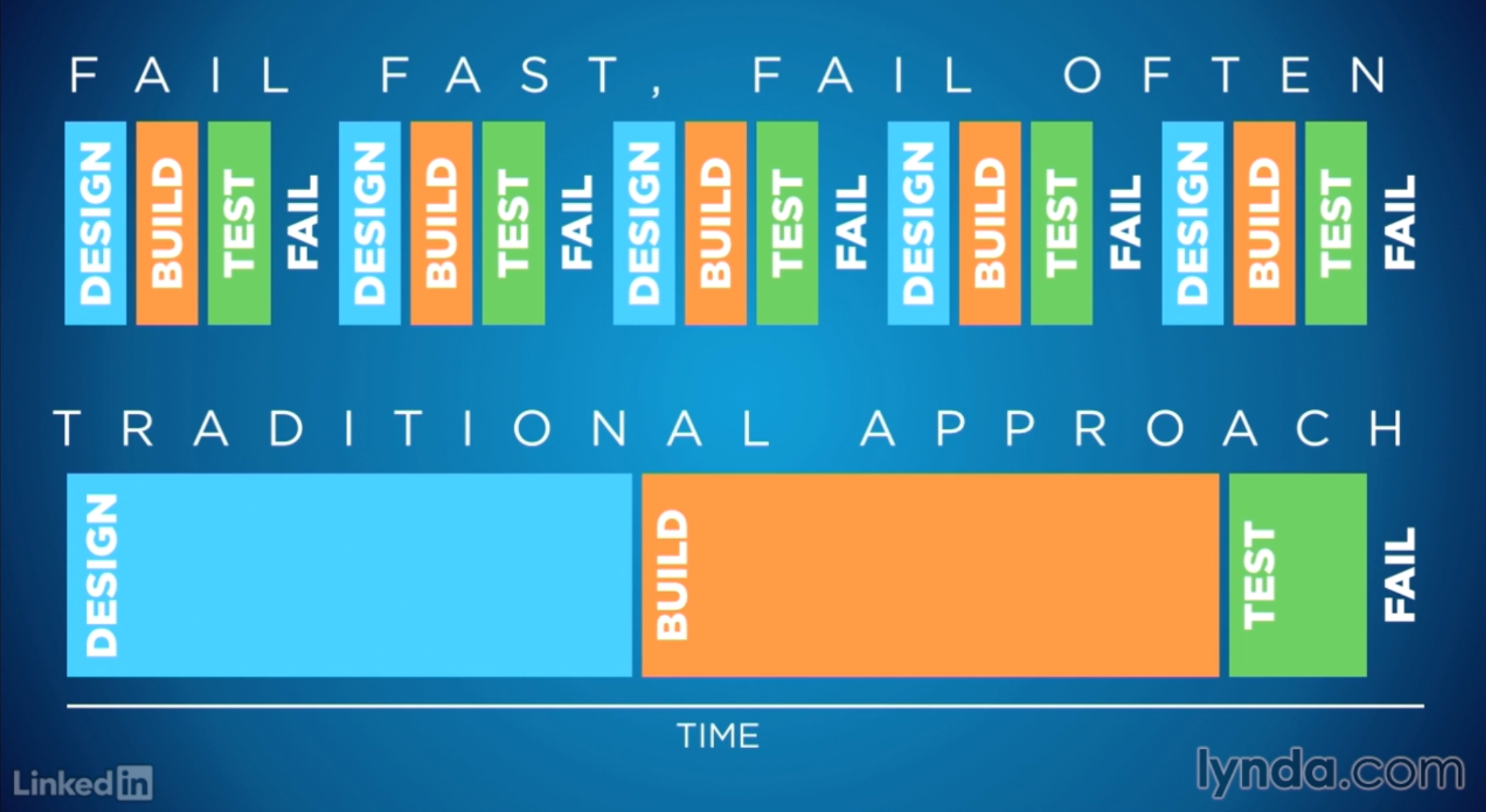

Enter the aeronautical engineer Paul MacCready. MacCready knew that the big P problem was not making a human-powered plane but speeding up the design-build-test cycle to learn how to make a human-powered plane, replacing theory and conjecture with real-world testing. By focusing on designing a plane that could be rebuilt in hours versus months, MacCready enabled his team to dramatically speed up iteration, which correspondingly sped up their learning. Six months later, MacCready’s Gossamer Condor flew over 2,000 meters, claiming the first Kremer prize. MacCready approached this problem assuming that a lot of failed prototypes are going to be required to solve the problem. And so he focused on getting through them as fast as possible. The phrase “fail fast, fail often” is based on this philosophy. Contrast this with a more traditional approach of spending a lot of time up front doing analysis, planning, and design to build the perfect beast and then expecting it to work the first time out. Even people who intellectually know the perils of this approach often fall into the trap.

Takeaway

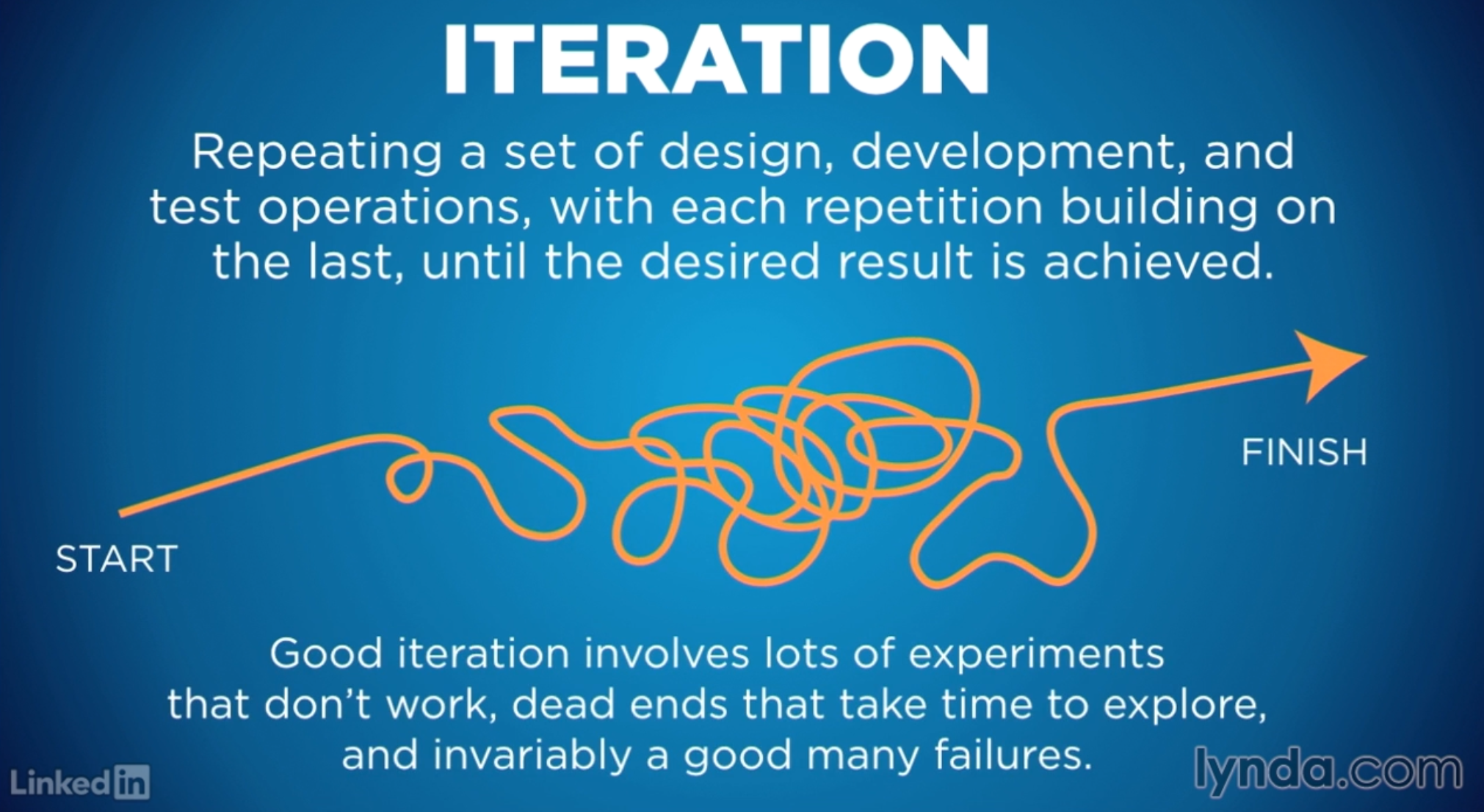

Iterative design is not a clean, linear process. Good iteration involves a lot of experiments that don’t work, dead ends that take time to explore, and invariably a good many failures. But failure in an iterative paradigm is not the end. It’s just another iteration from which you learn. I often liken design iterations to rungs on a ladder of understanding. No great heights can be achieved without climbing a lot of them. A fundamental lesson of iteration relates to another principle of design referred to as Gall’s Law. Gall’s Law states that all complex systems that work evolved from simpler systems that worked. The implication is that if you’re designing a complex system, a physical product, a software application, a business process, whatever, you should start by designing and building a simple system first, learn what works and what doesn’t, and then improve it iteratively over time. This seems like the long way of doing things to the uninitiated, but trying to shortcut this process is futile. It will take longer, cost more, and have a higher probability of terminal failure. So whether you use iteration to develop great products and services, invent the next killer app, or win the next Kremer prize, there are still two prizes unclaimed, by the way. Remember, the long way is the short way to get there.